In the far reaches of our Solar System, there’s a mysterious world called Eris. This distant dwarf planet holds surprises that make us rethink our knowledge of the Solar System. But when was Eris discovered? How did Eris get its name?

In this article, we’ll briefly explore Eris’ discovery story and the people behind uncovering this distant, icy orb. We’ll look at how Eris was initially spotted during a wide-field survey searching for remote celestial objects beyond Pluto.

Join us on a quick tour behind the discovery of this remote, icy dwarf planet!

When Was Eris Discovered?

Eris, a dwarf planet in our Solar System, was discovered on January 5, 2005, by astronomers Mike Brown, Chad Trujillo, and David Rabinowitz at the Palomar Observatory in California.

Its identification led to the reevaluation of the classification of celestial bodies in our Solar System and played a crucial role in the discussion surrounding the definition of a planet. This discovery contributed to our understanding of the outer Solar System and the diversity of objects residing beyond Neptune’s orbit.

Mike Brown’s Role in the Discovery

Mike Brown played a pivotal role in the discovery of Eris in the outer Solar System. In 2005, Brown and his team identified Eris in their ongoing survey to explore the Kuiper Belt. Eris’s discovery was groundbreaking as it challenged the classification of Pluto as the ninth planet, leading to the reevaluation of what constitutes a planet.

Brown’s work expanded our understanding of the Solar System’s dynamics and prompted the International Astronomical Union (IAU) to redefine the criteria for classifying celestial bodies. This reclassification marked a significant shift in how we categorize objects in our Solar System, distinguishing between planets and dwarf planets.

Mike Brown’s contributions to the discovery of Eris had profound implications for planetary science, reshaping the way we conceptualize the diversity of celestial bodies in our cosmic neighborhood. His research continues to influence astronomical discussions, emphasizing the importance of ongoing exploration.

The Tenth Planet controversy

The Tenth Planet controversy emerged when Eris (2003UB313) was discovered by Mike Brown in 2005, challenging the traditional view of the Solar System. Initially labeled the “tenth planet,” Eris ignited debates on planetary classification.

The controversy prompted the International Astronomical Union (IAU) to reassess the criteria for defining planets. In 2006, a new classification system was established, making Eris a dwarf planet. This decision sparked discussions on the definition of a planet and highlighted the evolving nature of scientific understanding.

The Tenth Planet controversy underscored the need for precise definitions in astronomy. It emphasized the dynamic nature of our comprehension of celestial bodies in the vast expanse of the Solar System.

How was Eris discovered by the team?

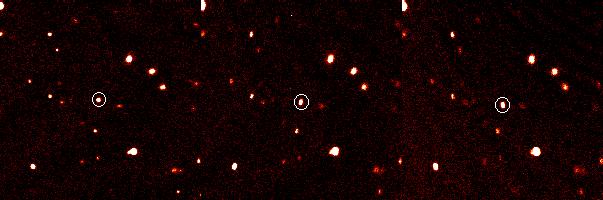

The discovery of Eris resulted from Mike Brown’s team utilizing the Samuel Oschin telescope at Palomar Observatory. Employing a systematic survey, they observed the outer Solar System over multiple nights. Eris was identified through the images, distinguished by its slow motion against the background stars.

The discovery expanded our understanding of the Kuiper Belt. It ignited the debate over Pluto’s planetary status, ultimately leading to the reclassification of celestial bodies and shaping our comprehension of the Solar System’s intricacies.

The Pioneering Trio: Brown, Trujillo, and Rabinowitz

As mentioned, Mike Brown, Chad Trujillo, and David Rabinowitz formed the team that discovered Eris in 2005. Mike Brown was a professor of planetary astronomy at Caltech. With expertise in observing Kuiper Belt objects, he played a lead role in discovering several large trans-Neptunian bodies.

Chad Trujillo was a postdoctoral researcher working under Brown at Caltech. His work focused on studying the outer Solar System. David Rabinowitz of Yale University brought experience finding other large KBOs, including Sedna.

This pioneering trio combined their talents to survey the edge of the Solar System. Using the Samuel Oschin Telescope at Palomar Observatory. They systematically analyzed images for faint, moving objects.

Their expertise with cutting-edge equipment and computational techniques enabled the discovery of Eris and many other Kuiper Belt denizens. Their revolutionary observations expanded the known Solar System.

Palomar Observatory: Unveiling Celestial Secrets

The Palomar Observatory in California served as the site for discovering Eris. Palomar Observatory is located north of San Diego and houses several telescopes operated by Caltech.

The Oschin Telescope enabled the detection of Eris with its advanced optics and digital camera technology. The instrument uses a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera that has been cooled to -148 °F to minimize noise.

It can image an area about 230 times greater than the moon in a single exposure. Along with computational techniques for processing massive datasets, the Oschin Telescope provided crucial tools to uncover faint objects like Eris beyond Neptune.

Classification as a Dwarf Planet

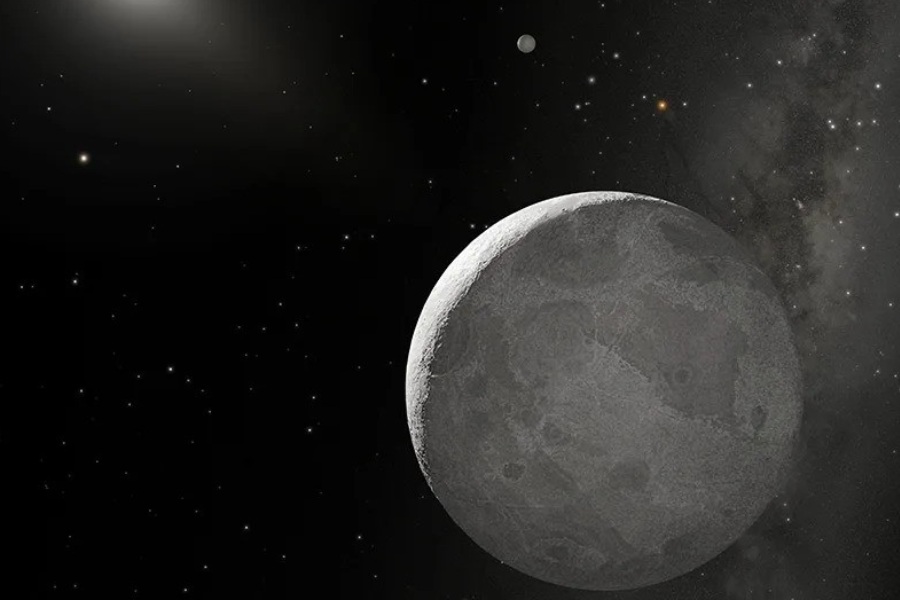

Eris was classified as a dwarf planet due to its size, shape, and location within the Kuiper Belt. With a diameter slightly smaller than Pluto, Eris failed to meet the criteria for a full-fledged planet.

In 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) redefined the classification of celestial bodies. Eris subsequently fell into the category of dwarf planets, characterized by their spherical shape yet inability to clear their orbits of other debris.

Situated in the Kuiper Belt, a region beyond Neptune populated with icy bodies, Eris shares characteristics with other dwarf planets in this area. Its orbit is highly elliptical, taking over 550 years to complete, and it resides among many small, icy objects.

The reevaluation of Eris’ status reflected a shift in our understanding of planetary criteria. It led to a more nuanced classification system that considers the dynamic nature of objects in our Solar System, especially those within the Kuiper Belt.

Physical Properties

Eris has a diameter estimated at 2,326 kilometers (around 1,445 miles), making it slightly larger than Pluto. It appears bright white, reflecting 86% of the sunlight that hits it. This high albedo results from a surface composed largely of frozen methane and nitrogen.

Moreover, Eris orbits the Sun in a highly eccentric path ranging from 38 AU at perigee to 97 AU at apogee. Its orbital period is about 558 years.

Unique traits

Eris, located far from the Sun, stands out due to its size. It’s the most massive dwarf planet, 27% more massive than Pluto. Eris has a uniquely inclined orbit, tilted 44 degrees compared to the Solar System’s plane. These characteristics highlight Eris as a significant icy world in the distant Kuiper Belt, offering insights into this mysterious region.

Eccentric orbit

Eris’s orbit is notably eccentric, deviating from a perfect circle. With an eccentricity of about 0.44, Eris follows a path that takes it relatively far from the Sun at aphelion (its farthest point from the Sun) and considerably closer at perihelion (its closest point).

This eccentricity and its distant location in the Kuiper Belt contributed to the challenges in detecting Eris. The discovery of Eris prompted discussions and debates within the astronomical community, leading to the reclassification of Pluto as a dwarf planet and redefining our understanding of the Solar System’s outer reaches.

Conclusion

When was Eris discovered? The discovery of Eris in 2005 was a turning point for reassessing celestial objects in our Solar System. This dwarf planet’s size and orbital characteristics fundamentally changed the definitions of planets and led to Pluto’s reclassification.

Eris reshaped our perspectives and prompted new considerations around properly categorizing the diversity of spheres orbiting our Sun. Its pristine nature provides a unique window into our Solar System’s formative years.

We hope this journey into the history of Eris has helped elucidate the significance of Eris’s discovery and the resulting impacts that ricocheted throughout the astronomy community. This planetoid challenged conventional cosmological frameworks and offered new perspectives on our star neighborhood.