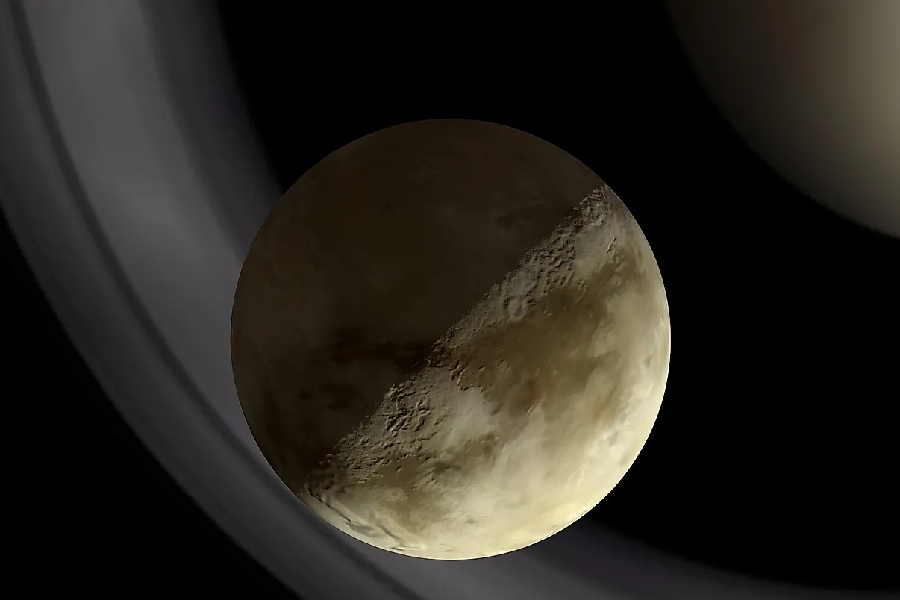

Shrouded under a thick, hazy atmosphere, Saturn’s moon Titan has perplexed astronomers ever since the invention of the telescope. This curious moon, with its strange chemical makeup and hidden surface, has remained one of the most intriguing objects in our solar system.

When exactly was this enigmatic moon first observed? The exact time of when was Titan discovered has been a source of debate and confusion over the years.

Throughout the centuries, persistent astronomers sought to reveal Titan’s secrets through gaps in its opaque atmosphere using the latest technological innovations. Yet the precise date of Titan’s definitive discovery has been difficult to confirm.

The timeline of Titan’s discovery is filled with claims and counterclaims of sightings by resourceful astronomers equipped with the telescopes of their time. Separating truth from speculation has challenged researchers.

In this article, we will delve into the winding trail behind Saturn’s largest moon. Only by understanding the incremental progress made across generations can we fully appreciate the story of Titan’s discovery.

When Was Titan Discovered?

When was Titan discovered? Titan, Saturn’s largest moon and the second largest in our solar system, was discovered by Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens on March 25, 1655. Using a telescope, Huygens spotted this substantial moon orbiting Saturn while observing the night sky.

Titan’s discovery marked a significant milestone in our understanding of the celestial bodies in our solar system. It has since become a major focus of scientific study. This is particularly due to its dense atmosphere. Another reason is its potential for harboring unique organic chemistry.

The debate over who discovered Titan

Huygens reported seeing Titan in 1655, but he was unsure, as gaps in the atmosphere allowed only a glimpse of Titan. Cassini later made a conclusive sighting in 1671. Astronomers debated Huygens’ claim since Titan’s thick atmosphere concealed it, making verification difficult for early telescopes.

Cassini used a more powerful telescope, ending the debate on discovery. However, astronomers still argued over details, as exact dates and times remained unclear, with historical accounts leaving gaps. Modern analysis tries to fill those gaps.

In 1944, Kuiper pored over records, wanting to settle lingering questions. But new analysis brought new debate, as the reliability of some observations was doubted. The debate continues today with no consensus on the discoverer. Credit is split between Huygens and Cassini, both of whom contributed key early observations. The final resolution depends on how one defines “discovery”.

Early observations and uncertainty

Huygens first saw Titan in 1655, but his telescope was too weak to be sure. Titan remained hidden behind a thick haze, so the observation could not be confirmed. For over a decade, no sightings were reported as Titan’s atmosphere obscured its surface.

Amateurs doubted Huygens had observed Titan, and his claim was largely forgotten. Superior telescopes arrived in the 1660s. After 1665, Cassini turned them on Saturn. By 1671, Titan was unmistakably seen, finally laying all doubts to rest.

Cassini’s observations clearly revealed Titan, though its surface remained obscured from view. Still, the discovery of this new Saturnian moon was now settled. This gave new credence to Huygens’ early disputed account.

Greek mythology and the Galilean moons

Greek mythology influence

Titan was named for the primeval Titans, Greek gods from old myths. Titan still bears this ancient mythological name. Other moons are also tied to mythology. Saturn’s wife was named Rhea in the myths, so the moon Rhea is so named. Iapetus was another Titan god, and a moon is named in his honor.

Ancient astrologers knew of Saturn’s moons and tied their motions to mythic stories. But little actual knowledge existed as mysteries were concealed by primitive telescopes.

Myths instilled awe and wonder; the public saw the moons as related to gods, while astronomers lacked data to refute the mythology. Superstition thus reigned for centuries afterward.

Galileo’s legacy – From drawings to discovery

Galileo first viewed Titan in 1610, but his telescope was too weak to discern details. Titan seemed to have merged with Rhea. Still, Galileo shared his observations, which showed Saturn’s “ears”. Misperceptions arose from this and persisted for years until later when Cassini used better telescopes.

Conclusively discovering Titan in 1671, with myth-making dispelled by data. Galileo’s views challenged prevailing myths as his works championed evidence over faith.

In time, findings revealed the natural order, and the scientific age dawned. Research into Saturn and Titan continues today, started by Galilean evidence disproving fanciful myths. Understanding is still shaped by his enduring legacy, where hard facts now rule in science.

Giovanni Domenico Cassini’s 17th century studies

Giovanni Domenico Cassini studied Saturn extensively for over 40 years through advanced telescopes. Making many breakthrough discoveries about its moons by tracking their positions and motions.

In 1671, Cassini definitively spotted Titan for the first time and calculated its orbital period and motion around Saturn. Over the ensuing decades, he further tracked Titan’s changing path to reveal details about its orbit, angle, and velocity shifts.

Despite only having hazy telescope views hindered by Titan’s atmosphere, Cassini greatly impacted planetary science. The Cassini spacecraft is now named for him. His telescope observations opened the door to the modern study of Saturn’s once mysterious moons.

For Titan specifically, Cassini logged changes in its appearance over time as its atmosphere seemed to irregularly thicken and thin. This drove future exploration to unveil more of this dynamic moon’s secrets.

The 18th Century Studies

In the 18th century, more powerful telescopes advanced studies of Saturn’s moons. Refractors improved to reveal new details about Titan’s surface and Saturn’s rings.

Famed astronomer William Herschel studied the Saturn system and noticed Titan’s fuzzy appearance, its blurred edges, and changing views over time. In 1789 he suggested it has a substantial atmosphere. This theory was later validated.

Additionally, seven new Saturnian moons were discovered in the century after Cassini, as telescopes became powerful enough to spot them. Reflector telescopes then utilized larger mirrors, producing brighter, clearer images and new insights. The Saturnian moon family continued growing as Enceladus and six more moons were revealed through the 1800s, crossing new discovery thresholds.

William Herschel’s discovery of Enceladus and Mimas

In 1789, William Herschel discovered the moon Enceladus orbiting Saturn using his advanced telescopes. This demonstrated the power of new tools and opened the door to finding more satellites. Just two years later, he discovered Mimas orbiting nearby. However, Mimas’ faint signal was easy to lose in Saturn’s glare.

These two new moons, unseen before, furthered Cassini’s earlier mapping and pushed the known Saturn moon total to seven. Finding more circling moons shed light, revealing complexity beyond just Titan and gaps likely carved by moon gravities.

Specifically, Enceladus orbits within the rings and feeds one, explaining their matching composition. Cassini later confirmed Enceladus has geysers.

Mimas defines the outer ring edge, sculpting the boundary and preventing accumulation. Discovering Enceladus and Mimas provided new pieces to solve puzzles and improve models for mapping the moons’ dynamic orbits.

John Herschel’s 1830 discoveries

John Herschel expanded on his father William’s work. Discovering Saturn moons from South Africa using the same powerful telescopes with speculum mirrors. In the fall of 1847, he discovered the moons Hyperion, Rhea, and Iapetus within weeks. Irregular Phoebe was detected in December.

John Herschel doubled the known Saturn moon count from seven to 15, overturning assumptions. Phoebe orbited backward, unlike other moons. His discoveries spurred dividing Saturn moons by type – nearby round moons in one group, with distant irregular-shaped moons like Phoebe in another.

Specifically, tumbling Hyperion added to the inner moon count with its irregular shape. Iapetus swept up dark dust on one hemisphere, hypothesized to be from Phoebe debris. Phoebe revealed clues on origins as a captured centaur world thought to be the dark dust source still darkening Iapetus over eons.

Conclusion

Tracing when was Titan discovered reveals incremental revelations and debates. As we followed Titan’s winding journey, the age-old question has hopefully become clearer now.

Throughout history, many observers glimpsed Titan through their telescopes. But definitely answering when it was discovered is complex. It has relied on assembling evidence within astronomical records that span centuries.

Fully grasping the challenges of unveiling Titan requires appreciating persistent astronomers’ efforts. We had to stand on the shoulders of each generation before space age capabilities existed to pierce the shroud.

The concept of “discovery” emerges as a tapestry woven across time. Dedicated scholars unraveled Titan’s mysteries thread by thread. They worked tirelessly to pull knowledge from within Saturn’s concealing veil.