Among the most intriguing of planetary discovery stories is that of Uranus – the icy giant planet invisible to the naked eye. But when exactly was this distant, hazy world first spotted in the depths of space? We will unravel the intricate story behind discovering Uranus and finally answer when was Uranus discovered, who discovered Uranus, and how.

Shrouded by the limits of primitive optics and its remote position, Uranus’s very slow movement eluded recognition as a planet for decades. Yet speculation through the ages gave way to dedicated telescopic sweeps that exposed this curious celestial object’s true identity.

Nevertheless, scientifically verifying the enigmatic sighting as a bona fide new planet rather than a comet or star perplexed astronomers worldwide over subsequent years.

The rich history behind Uranus’s revelation showcases the determined efforts of astronomy’s early pioneers. We’ll uncover who the key players were in unveiling the seventh planet from the Sun.

When Was Uranus Discovered?

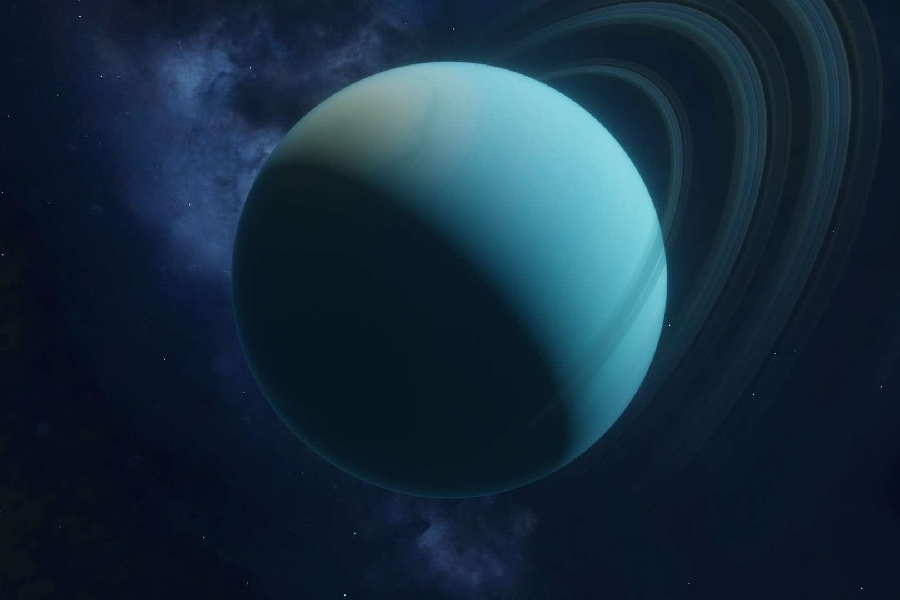

When was Uranus discovered? Uranus was discovered on March 13, 1781, by astronomer Sir William Herschel. While observing the night sky, he identified a new celestial object. Confirming it as a planet, this groundbreaking discovery occurred in Bath, England, expanding our knowledge of the Solar System.

Herschel’s finding marked a pivotal moment in astronomy, revealing the existence of a new planet beyond Saturn and Jupiter and forever changing our understanding of the cosmos.

Prehistoric awareness

Prehistoric or early human awareness of Uranus

Uranus is barely visible without telescopes due to its faint glow and slow movement across the sky. There are no records indicating humans were aware of Uranus before the invention of optics. However, ancient people did observe and keep track of the visible planets, signaling an interest in celestial wanderers.

While some theories speculate monuments like Stonehenge correlate with planetary alignments, there is no confirmed evidence involving the position of Uranus specifically.

Additionally, ancient understanding did not characterize celestial objects into the same distinct planet categories we employ today. Overall, Uranus’ dim, undiscovered presence testifies to necessary advances before unlocking awareness.

The role of Uranus in ancient cosmology

Babylonians detailed the movements of Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn in early cosmology models. Uranus likely only entered naked eye views during rare brightness bursts. These brief occasions went unrecognized as a single planet up through the modern astronomy era.

So, Uranus played no confirmed part in early cosmological frameworks across cultures. Only with improved optics did clues emerge to fully expose Uranus as the next planet from Saturn.

It lingered at the frontier of human perception, occasionally brightening as if to announce itself before fading into obscurity between background stars.

Ancient Greek astronomy

Ancient Greek insight into Uranus

While the ancient Greeks lacked telescopes to directly observe Uranus, their concept of the cosmos influenced the naming of the planet. There are no confirmed records of the Greeks observing Uranus, even near its brightest point.

The planet’s name, however, reflects a tribute to the legacy of early astronomers. Uranus, the Greek god of the sky, represents the vastness and wonder the ancient Greeks saw in the heavens. This connection honors the trailblazers who laid the groundwork for later astronomical discoveries.

Greek astronomers’ celestial contributions

Pioneers like Aristotle realized viewing all stars as fixed was incorrect. This seeded seeking understanding of wanderers versus fixed night sky objects. Later, Greek models organized movement patterns enough to aid future planet identification from Earth.

Though not directly involved in Uranus’ eventual discovery, Greek astronomical insights established foundations adopted in the modern astronomy era. These foundations laid the groundwork that made finding new worlds like Uranus possible.

Ancient Babylonian and Persian astronomy

Babylonian and Persian astronomers and Uranus

Like the Greeks, early Babylonian star catalogs and movement tables laid astronomy foundations. But Uranus’s limited visibility kept it hidden without telescopic aid. Some speculate on links between old records mentioning “the white star” to Uranus.

In 964 AD, Persian astronomer Al-Sufi noted a faint “little cloud”. Modern analysis suggests this first recorded sighting of Uranus. Yet, lacking adequate technology, just one brief glimpse proved insufficient to reveal Uranus as a planet. The key obstruction was an inability to closely track the object’s motion or details revealing its planetary nature.

Ancient civilizations’ celestial contributions revealed

Babylonian astronomers created detailed records of night sky motions. Persians made key observations like Al-Sufi’s. While not directly naming Uranus itself, these Middle Eastern accomplishments pointed later astronomers toward undiscovered worlds.

This scanning led to the pivotal sightings and tracking needed to determine Uranus as a planet. So foundational work collecting data and observing enabled the later pivotal revelations revealing Uranus conclusively.

Progress came in phases – ancients mapped the visible realm while dreamers unearthed clues to unlock opaque frontiers for the visionaries who followed.

The Discovery of Georgium Sidus (Uranus)

Herschel’s discovery

Amateur astronomer William Herschel was surveying the night sky when he noted an unusual celestial object in 1781. Investigating this anomaly revealed the first planet sighted since antiquity. Herschel distinguished this new world by its size and orbit over months of meticulous observations. Initially, characterizing it as a comet soon proved incorrect – further tracking cemented it as a true new planet.

In serendipity, the very night Herschel revealed the nameless wanderer would expand conceptions of our solar system. As evidence accumulated, a vision emerged of seven siblings welcoming an eighth cosmic traveler.

Herschel proposed the name “Georgium Sidus”, or the Georgian Planet, for his verified discovery in honor of England’s King George III. This recognized the monarch’s support amid ongoing battles with France during the planet’s identification period from 1781-1783.

While this patriotic name faded as German astronomer Johann Bode’s suggestion of Uranus arose, Herschel’s key observations marked a monumental expansion of humanity’s understanding. His observations expanded the known bounds of our solar system.

In-depth process and key identification elements

William Herschel crafted his own reflecting telescopes to pursue astronomy in his spare time from musical interests. Nightly scans seeking double stars in 1781 exposed one stellar object exhibiting strange properties. Confirmed movement over months of new sightings convinced Herschel it was likely an undiscovered planet.

Herschel’s home built telescope featured a 12-inch metal mirror – very large for its era. This and pristine dark country skies enabled his unexpected catch. Noting the object much dimmer than stars but over ten times larger was key, this assessment focused on it as exceptional over years of daily celestial monitoring.

Meticulous position charting revealed dramatic movement definitively inconsistent with parallax or known comets. Sharing these data with academics at the Royal Society verified Herschel’s historic seventh planet deduction.

Titius–Bode law in the 19th century

The Titius-Bode equation predicted planets would orbit at defined relative distances from the Sun. Confirming a missing planet between Mars and Jupiter strengthened the model. Spotting Uranus now at the law’s next predicted position out from Saturn provided even greater 19th-century proof.

This proof confirmed the potential of the Titius-Bode law to estimate planet locations. While not a true physical theory, the neatly matching mathematical harmony of the Titius-Bode law lent insight into the Sun’s family of worlds.

This revelation inspired discovery efforts that next led to Ceres and the main asteroid belt in place of the formula’s missing planet. The law’s success boosted acceptance of Herschel’s object as the next great celestial wanderer – Uranus.

As numbers aligned uncannily with sightings, confidence grew in both model and confirmation – formula supporting observation supporting formula.

Subsequent Findings About Uranus

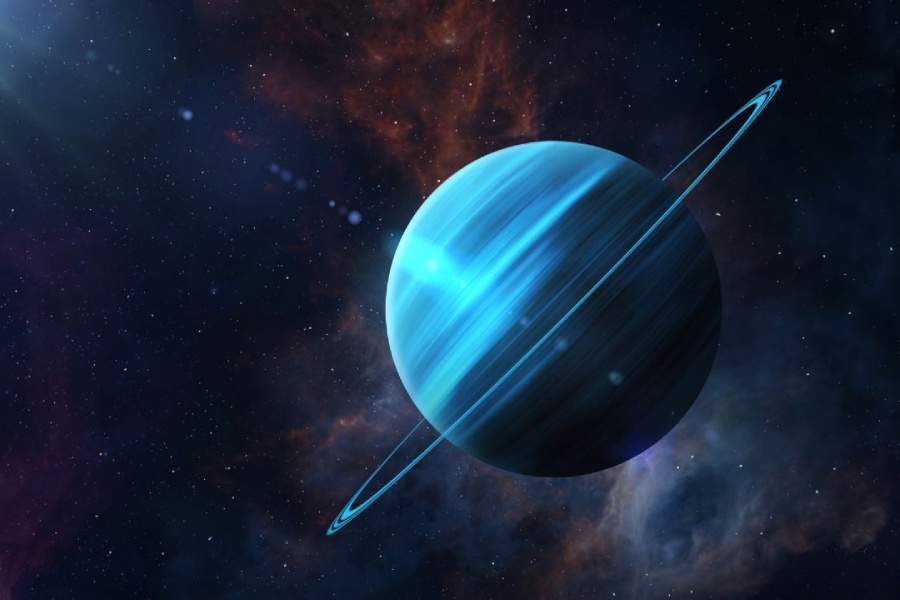

Later astronomy soon exposed Uranus had moons and was a gas planet – not Earth-like. Its odd tilt prompted Neptune’s find correcting earlier orbits. Modern reconnaissance like Voyager 2 imaged the puzzlingly bland world up close while discovering more moons.

From a faint smudge in old telescopes, Uranus has grown into a complex system. Its methane atmosphere and bizarre axial tilt remain enigmatic, waiting to be understood.

As we have gained rich insights from visiting Saturn, Jupiter, and beyond, Uranus beckons for future dedicated probes to unveil its mysteries.

Just as Herschel first glimpsed this ice giant, deeper study may yet reveal profound findings about the outer Solar System’s workings. What new innovations must yet emerge to lift the veil on this remote orbital realm?

Conclusion

This exploration has traced the fascinating journey of Uranus’s discovery. We delved into the mysteries of early observations and the naming story that unfolded over centuries, culminating in 1781.

Throughout this journey, we’ve witnessed the remarkable convergence of celestial detection challenges and unwavering human determination.

The unlikely yet fruitful partnership between William Herschel and King George III exemplifies this spirit. Their dedication led to the first glimpse of the faint and distant Uranus, answering the question of when was Uranus discovered.

While the king’s proposed name, “Georgium Sidus”, didn’t endure, Uranus, the Greek god of the sky, became a fitting tribute. This discovery not only unveiled a new world but also hinted at the vastness of the Solar System, with more planets waiting to be found beyond Saturn.

From a fleeting observation of the unfamiliar, a profound understanding emerged. Uranus, like an uncut jewel, holds secrets yet to be revealed, inviting future exploration to unveil its hidden facets.